The Story of “The Village Sign” – and the history behind it…

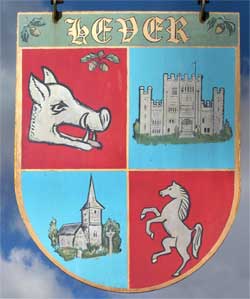

In 1995 it was decided that Hever should have a Village sign, and the Residents Association took on the task of designing and producing one.

Together with the Parish Council, the following criteria were decided upon: –

- It should reflect the most important and historical aspects of the Village.

- Although it should work at full (Inn Sign) size, it should also be clear enough to be reduced to work as a logo on letterheads etc.

- With this in mind, it had to work both in colour and monochrome.

- Once the design was agreed, it should be freely available for any Village based group to use.

Hever Castle (part 13th century) and St Peters Church (part 12th century) were obvious choices for inclusion, and their relevant authorities were happy to give consent for their respective logos to be used. Both have their own websites which give much more information on their histories and origins than could be included here.

It was obviously important to include something which depicted the origins of the name Hever, and the ancient settlement that became the Village. It was also decided to include the prancing white horse, the logo of the County of Kent.

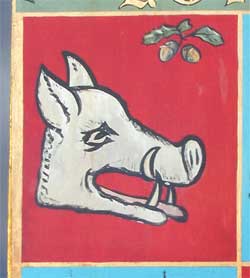

The origins of ‘Hever’ go back at least to the Iron Age and probably before. The little settlement was on the fringes of a dense oak and beech forest known as the Andredswald – ‘The Place Where No Man Dwells’. Nonsense, of course. Plenty of people lived there, but it was a lawless region which strangers entered at their peril. Little of the forest now remains and the old name became corrupted to today’s Weald. The forest was home not just to people, but also to a thriving population of wild boar.

By the time the Romans arrived, in the first century AD, some enterprising locals had taken advantage of this natural resource, and were raising piglets in captivity, to provide a year round source of sweet, tender meat. There was a convenient site on the banks of a river which was known as ‘The Pig Pen Under the High Bank’, soon shortened to just ‘High Bank’. In old English this was ‘Hean Yffrge’.

A nearby settlement, comprising Eadhelm’s family, boasted a substantial bridge across the river. The Romans built a road which utilised Eadhelm’s bridge (today’s Edenbridge), the course of which can still be seen on modern maps. It runs in a dead straight line from Limpsfield in the north, down through Edenbridge High Street and south to the A264, where the remains of the old road can still be seen. To the west of the road, above Den Cross, the site of an unexcavated Roman Villa is shown on O.S. Maps.

The new Roman settlers quickly developed a taste for suckling pig, leading to prosperity for the inhabitants of Hean Yffrge, and a rapid expansion of its population. It was, for the first time, a village in its own right.

The Romans left, new waves of invaders followed, but it wasn’t until the 11th century and the Norman Conquest that old English, with its guttural vowel sounds and glottal stops, finally began to die. The French speaking Normans simply couldn’t pronounce it. So ‘Hean Yffrge’ became variously Hévère, Heuvre, Heanve, etc. By the end of the 15th century it had more or less settled to Hever, the name it bears today.

The old high bank survived as a geographical feature until 1903, when William Waldorf Astor bought Hever Castle, and had the surrounding estate landscaped. Today there is a large lake where once piglets were raised.

So, the village sign bears a stylised version of a boar’s head; the kind used in heraldry, and with oak leaves and acorns to symbolise the ancient forest.

The final quarter of the sign bears the white horse, the logo for the county of Kent. Back in the 5th century AD, after the Romans had gone, the land of the Britons reverted to being a collection of small kingdoms, one such being Cant, or Kent (Hence Canterbury). One particularly powerful ruler was King Vortigern, who controlled not just Kent but other Kingdoms all over present day England and Wales. Without the powerful Romans to curb them, the Picts and the Scots were surging across the borders, taking land by force, and threatening the British Kingdoms.

The final quarter of the sign bears the white horse, the logo for the county of Kent. Back in the 5th century AD, after the Romans had gone, the land of the Britons reverted to being a collection of small kingdoms, one such being Cant, or Kent (Hence Canterbury). One particularly powerful ruler was King Vortigern, who controlled not just Kent but other Kingdoms all over present day England and Wales. Without the powerful Romans to curb them, the Picts and the Scots were surging across the borders, taking land by force, and threatening the British Kingdoms.

Vortigern appealed for help, first to the Romans, and then to the Germanic tribes of Europe – the Angles, Jutes and Saxons. The Saxon Prince Hengist responded, bringing with him his brother Horsa and an army of fighting men. Vortigern granted them the Isle of Thanet as a base, and in due course the Pictish invaders were driven back, peace reigned, and Vortigern added Hengist’s daughter, Rowena, to his collection of wives.

But the warlike Hengist was hungry for more land, and turned his troops on his erstwhile ally. Thus Hengist became King of Kent. Hengist means ‘stallion’ and the prancing white horse, his symbol and shield-protector, became the symbol of his kingdom. Hengist then invited more of his European allies across the water, and waves of invading Angles, Saxons and Jutes duly settled all over present day England, driving the native Britons ever further south and west. Their descendants were eventually confined to Wales and Cornwall, and what had been Briton-land (Britain) became Angle-land (England).

Six hundred years later, in 1066, William of Normandy invaded, and as everyone knows, won the Battle of Hastings and became King of all England. It wasn’t quite that simple, though. Having settled his power base in London, William was then faced with a series of rebellions. William’s troops had just successfully quelled a rebellion in the North, and were marching back to London, when word was brought to the King that the usually warring Kentish Men and Men of Kent had joined forces and were marching on London.

William’s battle weary troops were in no shape to immediately face another insurrection, so instead the Conqueror agreed to parley with the Kentish Leaders. In return for an undertaking not to mount any further rebellions, William granted Kent, alone in the entire Kingdom, the right to consider itself unconquered. A jubilant army returned to Kent, and from that time the white horse logo had a banner added to it, bearing the single word ‘Invicta’ i.e. ‘unconquered’. To this day, Kent is proudly independent, even though its significance these days is only symbolic.

Today, the Village Sign hangs from the arm of the Beacon Post, on the Parish Field opposite the King Henry VIII Inn, in the centre of the village.

This Village has a long and proud history, and we hope you have found this brief résumé informative and interesting.